Infra

Mayor Olivia Chow’s city hall inconsistently addresses antisemitism in Toronto, according to complaints

It’s been a rocky year for relations between the Jewish community and Toronto’s municipal government following the Oct. 7, 2023, assault on Israel—which led to an ongoing regional war in the Middle East and corresponded with repeated anti-Israel demonstrations and attacks on Jewish institutions in Canada.

Local and nationwide organizations have urged their elected representatives to demonstrate stronger leadership in condemning antisemitism in Toronto. But the responses they report receiving remain largely lukewarm.

Mayor Olivia Chow’s absence at the Oct. 7, 2024, memorial event organized by UJA Federation of Greater Toronto—attended by multiple federal parliamentarians, Ontario premier Doug Ford and other provincial lawmakers, along with several city councillors—amplified the perception that the mayor’s support is lacking.

It’s a thread of criticism that started over a year ago when the mayor’s office posted remarks attributed to Chow a few hours after the Oct. 7 Hamas attacks, which were publicly posted and quickly deleted twice on social media before a final version was settled upon.

Chow’s handling of her no-show at the memorial did nothing to improve the Jewish community’s confidence in her support, already seen as inconsistent. The office of the mayor offered three separate reasons for her absence, including not having received the invitation.

Then came a TV news interview where Chow said “it doesn’t matter” why she missed the commemoration, but she ultimately apologized to the Jewish community. A petition urging Chow to resign for neglecting the Jewish community gathered more than 12,000 signatures during that period.

The imbroglio over the memorial exemplifies the disappointment many Jewish Torontonians associate with Chow. The sense of insult and political calculus linked to Chow has permeated, despite her apology.

Jewish advocacy groups say the community wants to see more leadership from Chow on condemning antisemitism when it shows up in displays of Hamas headbands, or a Hezbollah flag. Toronto police arrested two people on public incitement of hatred charges following a protest in late September where they continued to display the flag of Hezbollah despite officers’ warnings.

Chow also skipped the Walk with Israel in early June, which drew an estimated 50,000 people. That same weekend, Chow enthusiastically attended the annual Grilled Cheese Festival in Etobicoke—an appearance publicized a few days later with some extra-cheesy puns.

Later in June, Chow marched in the annual Pride parade (which she has regularly attended throughout her four-decade political career), but did not comment when a demonstration over sponsors’ Israeli investments led the parade procession to be halted prematurely—with some of the parade participants, and big crowds, still lining Yonge Street.

Some fences mended with mayor

The Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs (CIJA), which called out Chow’s no-show at the Oct. 7 memorial, met with the mayor, her chief of staff Michal Hay, and a UJA executive, at Chow’s office in October.

Michelle Stock, CIJA’s vice-president for Ontario, says she told Chow she wants her to take a tougher, more vocal posture in denouncing antisemitism. The mayor needs to show up more consistently for the Jewish community, says Stock—regardless of perceived political support for Israel.

Chow has appeared at a number of major events, including UJA’s emergency rally on Oct. 9, 2023, and a gathering of support following the first of two early Saturday morning gunfire incidents—which took place in May and October outside the empty Bais Chaya Mushka Elementary School in North York.

Stock maintains that “[Chow] needs to be clear… the Jewish community in Toronto are her constituents. We are taxpayers… we have a right to have law and order, to have safety in our streets, and feel that we can be openly Jewish and not feel like you have to hide that.”

Stock says she’d like to see Chow speak up unequivocally and that the mayor “needs to continue to show presence in the community” and “acknowledge the experience of the Jewish [community] in Toronto,” including demonstrations taking to Jewish neighbourhoods.

CIJA’s vice-president for Ontario adds that by not standing with the Jewish community, Chow, who campaigned on diversity and inclusion in her mayoral campaign, is creating the opposite effect.

“Hateful chants in [the] streets… terrorist flags at these protests, people dressing up like Hamas… those are unacceptable behaviours, and by her not going out and publicly denouncing these things and being very clear that she doesn’t want to see these things in her street[s]—and taking that leadership position—she’s countering what her brand is about: diversity and inclusion.

“She’s emboldening… more division in her city rather than bringing people together to find the common ground… the shared values we all have as Torontonians.”

Despite the Oct. 7 memorial letdown, Stock gives Chow credit for attending the Toronto Holocaust Museum on Nov. 4 for a tour and discussion on contemporary antisemitism during Holocaust Education Week.

Social media postings claimed the mayor made a hasty exit partway through the program—a falsehood amplified by independent downtown MP Kevin Vuong without a subsequent retraction or apology—but Stock confirms that Chow participated fully in the event, as scheduled.

“People had an opportunity to voice their concerns with her about what was going on in Toronto, and she gave people a lot of airtime.”

Bubble bill defeated at council

It’s not simply that Chow has not appeared consistently at Jewish community events, but that raucous anti-Israel protests have gone on throughout the city, which make some Jews feel protesters have gotten a free pass.

‘Bubble zone’ legislation which would have prevented protests near religious institutions was introduced to city council in October 2023—but councillors narrowly voted down the bylaw the following May, instead asking the city manager to devise an action plan and refer it to the police.

(Similar legislation has been passed in municipalities near Toronto, including Vaughan and Brampton.)

‘Keeping Toronto Safe from Hate’ came to the police board as a draft proposal in September. Following a unanimous Oct. 12 vote on a motion by Chow—one year after council adopted an initial motion of the same name around anti-hate measures—the city’s website launched a resource page for the initiative.

The plan covers six categories: infrastructure, legislation, community safety and funding, public education and awareness, incident management and response, and increased collaboration between the City of Toronto and Toronto Police Service.

The plan does not propose new municipal departments or entities, and instead draws on the city’s existing diversity, equity, inclusion, and community safety efforts, and policies “promoting respectful conduct, inclusion and an environment free from hate.”

In a statement from Chow’s office to The CJN, the mayor noted her support for the Jewish community included affirming a council motion in June from uptown York Centre city councillor James Pasternak—one of four of Toronto’s elected council members who is Jewish, along with Josh Matlow, Dianne Saxe and newcomer Rachel Chernos Lin—which was called “Fostering Belonging, Community and Inclusion, and Combating Hate in Toronto.”

The city committed to relaunch its Toronto For All anti-hate public education campaign with displays on city-owned bus shelters and benches, maximize safety on city streets through urban design, explore additional city funding for gathering spaces, and direct city staff to review the graffiti management plan to ensure there is a rapid response to hate graffiti.

Chow also signed a declaration from multifaith coalition Rally for Humanity, which Pasternak introduced at the most recent monthly meeting of city council.

Chow told The CJN in a statement she is committed to the safety and well being of Toronto’s Jewish community.

“There is no place for antisemitism in our city—full stop.”

This month, the police board passed a long-term hiring plan designed to boost the number of officers.

“This plan is responsive to the needs of Torontonians, including members of the Jewish community who have felt unsafe in our city over the last year,” wrote Chow, saying she’ll work with other levels of government to fund the plan.

Budget chief Shelley Carroll, a councillor and member of the police board, confirmed in a written response that the Jewish community was among those helping to “shape [the city’s] priorities” during pre-budget consultations that ended Oct. 31. (Carroll also confirmed the graffiti management plan has been updated “to respond quickly to hate-related incidents.”)

Speaking to The CJN last month, Pasternak—whose riding has a significant Jewish population—called bubble legislation an important step. But leadership and law enforcement are the key issues, he says.

“Our big problem is we are not getting universal condemnation and the strong law enforcement aspect that we need to stop… these hateful mobs. One of the most severe consequences [of those] since Oct. 7 is that they have left the city very vulnerable when it comes to law and order.

“From the Jewish community point of view, we want to see [TPS] get the resources they need to keep our city safe, to keep our community safe.”

Pasternak thanked community leaders when he introduced the declaration at council on Nov. 13, saying “government alone cannot do all the things necessary to keep the city liveable, safe and free from hate, and one of high purpose, through social cohesion.”

He told The CJN that protest bubble zones are a “crucial part of keeping our faith-based institutions safe” by creating spaces protesters cannot access.

But his colleague Josh Matlow of the midtown St. Paul’s riding–where the Jewish population is also significant— says that “community safety zones,” or bubble zones, and similar measures do not resolve the challenges the city’s Jewish community is facing, which Matlow says are too important for “symbolic gestures… that don’t mean, or achieve, anything.”

The initial bylaw was too broadly worded to be enforceable, he said.

“It didn’t focus in on the real problem, which is when members of the Jewish community are being harassed and intimidated by protesters.

“In many cases before Oct. 7, and certainly since, there’s been a heightened level of insecurity in Toronto’s Jewish community when it comes to their safety.

Jewish Torontonians want to feel “that the city and the police are doing everything they can to keep them safe,” said Councillor Matlow, including protecting Jewish spaces like schools, synagogues, and community centres, and enforcing existing laws.

“It’s really important that whenever any one of our communities is subject to hate and harassment and intimidation, whether that be Black, LGBTQ2S+, Asian, Muslim, or Jewish community, that leaders take a stand and make it very clear we don’t accept that… we stand with the community that’s being victimized.

“And what I hear from the Jewish community is that far too often they feel that they’re not treated that way.”

The new action plan is taking important steps, he says, with improved coordination between police and the city.

“The police have come a long way, and I think they’ve adapted their approach, working with the city. There’s still a lot of work to do, but I think that things have come a long way.”

Josh Matlow, meanwhile, continues to caution that the focus on places of worship—including several prominent Jewish institutions in his own ward—won’t entirely address the issue.

“The evidence has shown us that the vast majority of incidents where Jews in our city have been harassed, have been intimidated, have actually not been at synagogues,” he said.

“It’s, sadly, almost everywhere else: it’s been in parks… it’s been at Jewish-owned businesses.

“The reality is there’s no such thing as a safety [zone] in real life. What we need to do is actually address the surge in antisemitic incidents throughout our city… and that’s not as simple as suggesting that we’re going to create some magic safety bubble.”

The view from downtown streets

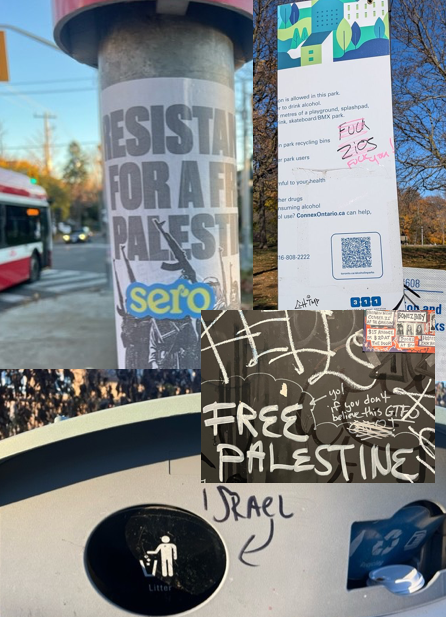

For some Jewish residents, there’s a sense that their local councillors have been ineffective in denouncing antisemitism, especially when it shows up as violent and anti-Israel images and graffiti.

Joanna Salit, who lives in the west-end riding of Davenport, where Alejandra Bravo is the city councillor, started a WhatsApp group for concerned residents, saying the graffiti on the streets that is violently anti-Israel makes her and others unsafe.

Salit initially met with Bravo in August, followed by another meeting in late September where she was joined by about 20 other concerned members of the Davenport group.

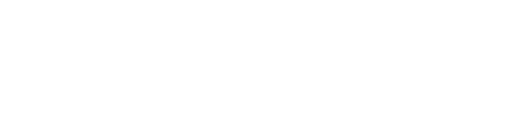

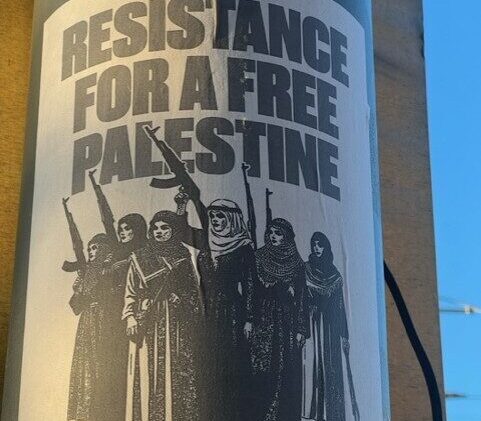

Posters and graffiti the community has found threatening and offensive include one recent flyer seen near Oakwood Collegiate, featuring “resistance” language alongside illustrations of women bearing assault rifles.

Salit says she’s tried to get Bravo to make public statements addressing harmful messages littering the area.

Toronto Police Service launched a web form for reporting hate-motivated graffiti in November last yearin the wake of the Oct. 7 attacks—and, in March 2024, TPS statistics showed 342 hate-related graffiti occurrences.

In a statement to The CJN, Bravo wrote that her office directs residents who report graffiti and posters to refer to the city’s process for removal under existing bylaws, and that TPS investigates reports of hate propaganda and hate-related incidents.

“Individual city councillors and their offices do not have the authority to direct bylaw enforcement or police enforcement activities,” she wrote.

“While views within Davenport and Toronto may diverge on global events, one thing is clear to me: Antisemitism is a scourge, and it is unacceptable. Hate speech and intimidation of any kind are unacceptable. I unequivocally condemn the recent occurrences of bomb threats, gunshots, and vandalism at Jewish institutions including synagogues and schools.”

Bravo also commented after an online video showed an antisemitic rant outside a mechanic’s garage on Geary Avenue. She recently denounced the attack on a mother outside the Chabad of Midtown pre-school—an affiliated location recently opened in her ward—which police are still investigating.

“Antisemitic hatred and violence is abhorrent and unacceptable in our communities,” Bravo posted on Nov. 15, after the attack.

Salit has emailed Bravo and Chow photos of the posters that call for “resistance” with assault rifles, and says she wants to see a strong stance against those, too.

“She [Bravo] really needs to be standing up for all constituents,” said Salit. “And say that Jew hatred in Davenport is not OK.”

Sarah Margles is a Davenport resident who attended the meeting at City Hall with Bravo, and says the failure in leadership she sees shows the need to establish and uphold common values in the city.

She says her city councillor’s office sent a warm reply to her offer to further discuss subjects like antisemitism on the left wing of the political spectrum, though Bravo’s office has not yet taken her up on the offer.

Margles’ sense is that what’s playing out in Davenport is part of a wider dynamic.

“The environment is so polarized, and not just on this issue,” she said.

“Jews here are feeling scared… feeling attacked because of what’s happening over there. That’s not cool. It’s also true about the experience of Muslims and Arabs and Palestinians who are feeling attacked here by Jews and the pro-Israel movement, and they’re also feeling attacked here because of what’s happening there. And that’s also not cool.”

City of Toronto officials, she says, are “also just dealing with rats and power outages… the real city things.”

When elected officials see signs around that say “resistance at all costs” with images “with a bunch of women holding guns,” they see that with different eyes than the Jewish community does, she said.

“The city needs a comprehensive way to look at ‘How do we deal with international clashes that blow up in our city even though the actual things are happening elsewhere, but the sentiment and the emotions and the fear and the anger are exploding here?’”

Margles says there’s a lack of leadership in taking that on.

“I don’t see them being clear about ‘Here’s what needs to happen in Toronto. We need to figure out how to not take our frustrations out on each other [if we are] upset about what’s happening around the world.”

Along with standing against antisemitism, and Islamophobia, she says, there’s often disagreement on the line between political advocacy and discrimination.

“We’re going to have to figure out how to carve those lines around ‘When is political advocacy tipping into discrimination or harassment of any group?’ And those policies need to be developed robustly and they need to be applied equitably to everyone.”