Bussiness

Downtown Toronto faces a crush of rising vacancies that could threaten building valuations

Downtown Toronto’s largest office landlords are plagued by a growing problem: too many empty floors.

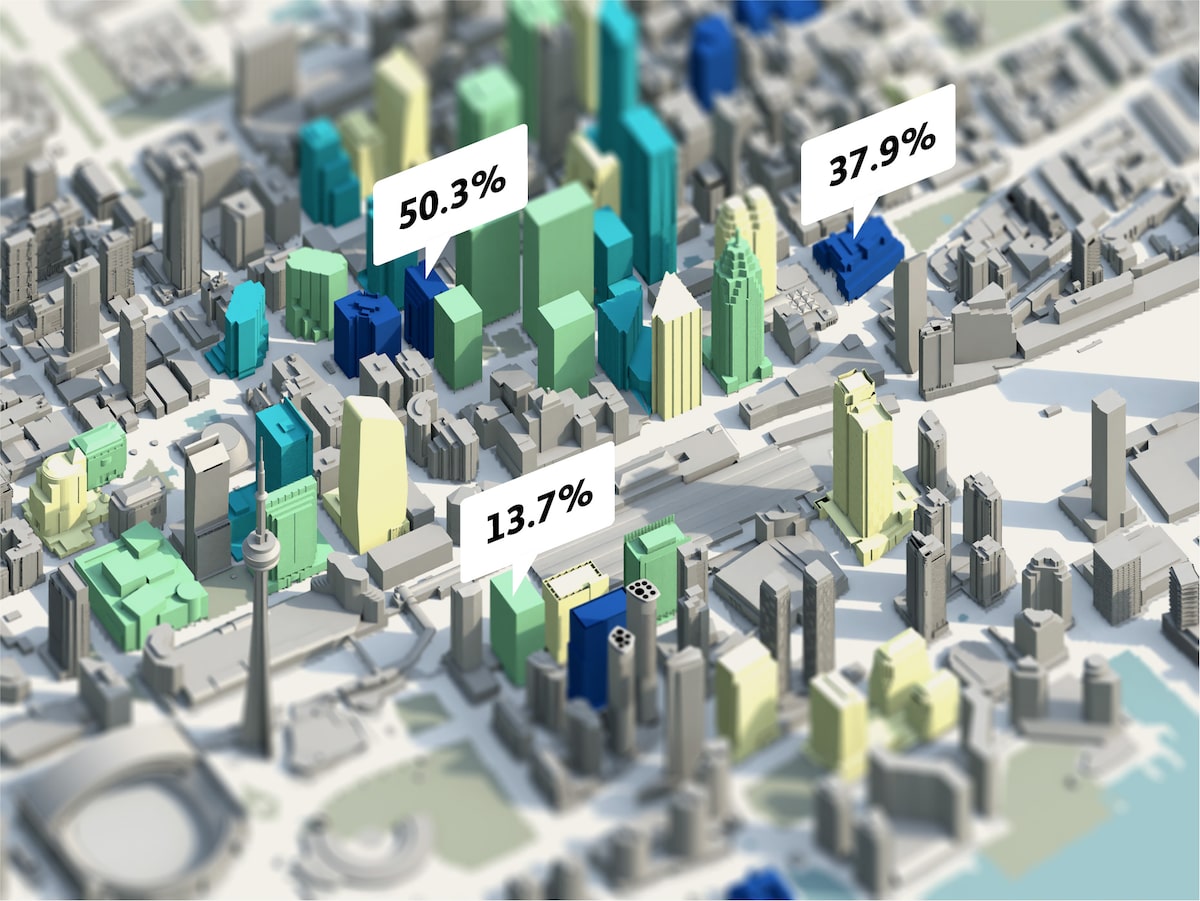

But all buildings are not equal, and a new analysis pulls back the curtain on what’s going on behind the shimmering glass of all those skyscrapers that define the city’s skyline, revealing a deeply divided office market.

While some towers are chock-full of tenants, one-third of the biggest office buildings in the core of Canada’s most important financial district are at least one-fifth empty, with some grappling with even larger voids of up to 50 per cent.

The characteristics of the fullest buildings provide insight into how landlords are navigating the new world of remote work at a time of high interest rates and a stalling economy.

It all raises questions about what might happen to valuations in Toronto’s office market if so much floor space remains left unfilled and what the effects on surrounding businesses will be. With some of Canada’s largest pension funds prominent landlords in the Toronto market, the implications go far beyond the power corner of King Street and Bay Street.

“Prior to the pandemic, downtown Toronto was a landlord’s market with very low vacancy and availability and since the pandemic it’s moved towards much more of a tenant’s market,” said Carl Gomez, chief economist and head of market analytics at CoStar, a Washington-based commercial real estate information provider that has operated in Canada since 2014.

Today, Toronto is one of the few Canadian cities where office vacancies are still on the rise. The percentage of space available to lease in the financial district was 17 per cent as of late April, according to CoStar, higher than the city as well as the rest of the country.

To drill beneath the headline number, The Globe asked CoStar to focus on a sample of larger buildings – those with a minimum of 400,000 square feet of rentable building area – in the financial core and south to Lake Ontario, but to also include one of Toronto’s most recent additions to its skyline, The Well, to the west of the core.

This resulted in a sample of 47 buildings, with a total rentable area of 38 million square feet, and includes Canada’s most eye-catching towers, such as TD Centre’s sextet of black skyscrapers, Brookfield Place and its glass atrium and Scotia Plaza’s red granite tower.

CoStar provided data on vacancy and availability rates for the buildings as of March 8.

The availability rate reflects the total amount of space that is being marketed and available for lease, including space that is vacant, up for sublet or set to come to market within 30 days.

The Globe and Mail reached out to the building owners to discuss the findings from CoStar’s analysis.

In most cases owners indicated their own internal numbers were within a margin of error for those provided by CoStar. Some owners disputed the availability rates but refused to provide their own numbers citing confidentiality reasons.

In instances where owners provided availability data significantly different from CoStar, the owner’s numbers are included in this story.

Mr. Gomez said CoStar’s availability data for a building may differ if, for example, an owner has short-term tenants in a space that is immediately available and considers the space occupied, which CoStar does not. Availability rates can change quickly too, and the numbers here reflect a snapshot in time.

“There is no perfect data for commercial space markets since it is not a very transparent sector, like the stock market where everything is publicly disclosed,” he said. “If a building owner takes exception to what we estimate, it is within their right as they are the only ones with complete information.”

One thing is clear: It’s a tenant’s market.

No longer can landlords profit simply from owning an office tower in Canada’s financial capital. Nor is easy access to the city’s underground path and public transportation enough to attract tenants. Owners have put in fancy showers, some have Dyson hairdryers, while others are providing activities such as trivia in the afternoon to entice tenants to love their office life once more.

Even those with high-profile skyscrapers have had to woo tenants with incentives such as more cash to improve their office space or a period of free rent.

The office tower with the highest availability rate among large buildings in the downtown core is the 40-year-old tower at 121 King St. W.

The building’s vacancies jumped after it lost one of its largest tenants, the Canadian Investment Regulatory Organization. As of early March, the office tower had an availability rate of 50.3 per cent and a vacancy rate of 42.3 per cent, according to CoStar.

Its owner, Crestpoint Real Estate Investments Ltd., which bought the building for $379-million in 2022, disagrees and says the availability rate was 39 per cent and vacancy was 28.5 per cent.

Nevertheless, Crestpoint has known the building needed to be overhauled, especially given the stiff competition from new skyscrapers.

“We knew it would require boldness,” said Max Rosenfeld, head of asset management for Crestpoint, the real estate arm of Connor, Clark & Lunn Financial Group Ltd., an asset management firm. “Softness in the market has forced landlords to be better.”

This is Crestpoint’s first building in downtown Toronto and it is rebranding the 25-storey office tower as RoseRock to reflect the building’s original material – the pink granite of the walls. It is radically changing the lobby with construction of a pink rockface that juts out over the escalators, inspired by Ontario’s rugged Killarney Provincial Park.

“We really wanted to distinguish the building,” Mr. Rosenfeld said.

Crestpoint also has some of the standard amenities that all the new buildings have – a bike room, showers and common spaces. RoseRock’s communal space on the 22nd floor will include meeting rooms, a bar, a library, a sports simulator and a patio with a view of Lake Ontario.

As the CoStar data show, the impact of the pandemic on Toronto’s office towers has not been even, with some towers seeing availability rates rise sharply while others have fared much better.

The most common explanation is that tenants are abandoning lower-class buildings to move into higher-rated towers with more amenities such as green spaces and cutting-edge ventilation systems, ditching Class C for Class A towers.

That’s certainly how many owners of buildings examined here see it:

But CoStar’s research suggests there’s more to the story than just quality. While availability rates in top-rated towers have held up better than lower-class buildings, a bigger shift has been from old to new. “Newer buildings built after 2015 are seeing significantly stronger demand than older buildings that are still five-star buildings,” he said. “This gets missed in the flight-to-quality narrative.”

That top tier of buildings, known as Class A properties, are located in prime locations with amenities such as a concierge, gyms and wellness rooms. These buildings command the highest rents and are coveted by tenants. The lowest tier, known as Class C, are in less convenient locations, generally older and have fewer amenities, if any.

The CoStar data reveal that newer Class A buildings built after 2015 had an availability rate of 2.8 per cent in the first quarter of the year. The older Class A office buildings had much more empty space with an average availability rate of 21.5 per cent in the same period, while Class C had an availability of 45.7 per cent.

Not all older Class A buildings have seen vacancies rise as sharply: 150 King St. W., a Class A tower owned by BentallGreenOak, the real estate arm of Sun Life Financial, was built in 1984. But it has an availability rate of 7.4 per cent, according to CoStar, a figure which BentallGreenOak spokesperson Rahim Ladha said is actually lower, at 3.6 per cent.

But for the most part, the age distinction stands. And the availability rate gap between old and new is widening.

Here’s another way to look at the interplay between age and availability.

The move from old to new was the case for the Canadian Investment Regulatory Organization (CIRO), which left the 40-year old building at 121 King W. when its lease expired. The investment industry watchdog moved in February to Bay Adelaide Centre North Tower, which was built in 2022 and has a 0.5-per-cent availability rate.

The watchdog group recently merged with the mutual fund overseer and wanted a fresh start for the new group and its hybrid work force. The group’s current location is about 15-per-cent smaller than its former space and its approximately 460 Toronto employees work in person in the office at least twice a week.

“Our new office is not only more suited to the hybrid working model, but also provides amenities that better promote a collaborative and productive work environment,” Joanna Nicholson, the group’s spokesperson, said in an e-mail.

The Well, built in 2022 and located just west of the financial district in an area teeming with condos, restaurants and shops, is an exception to the trend of newer buildings having lower availability.

The building’s main tenant, Shopify Inc., abandoned plans to move into the space and in early 2023 put its seven floors up for sublet. As a result, The Well had an availability rate of 39.2 per cent, according to CoStar. One of its owners, real estate investment trust RioCan, did not respond to a request for comment. Its other owner, Allied REIT, referred The Globe to its quarterly results which said office leasing activity increased over the previous year.

Shopify has a 15-year lease that requires it to pay rent on the space. Because its space is not being used, there are fewer people in the office building. That means fewer people buying coffee at the new cafe and shopping at the other surrounding retail, though The Well is surrounded by condos and gets foot traffic from the neighbouring residents.

Retailers near emptier buildings in the financial district aren’t so fortunate.

The return of foot traffic to downtown appears stalled. The share of employees in Toronto’s financial core has been stuck at about 60 per cent of prepandemic occupancy since early February, according to consulting group Strategic Regional Research Alliance. The peak day is Wednesday at 70 per cent and the lowest is Friday at 37 per cent.

Businesses have marvelled at how easy it is to find space in coveted buildings. Accounting and business advisory firm MNP LLP said it got a prime location at a 30-per-cent discount to prepandemic days. CIRO, the investment watchdog, said it had a number of properties to choose from.

A flood of new office space has come onto the market in recent years. Since the start of the pandemic, 11 downtown office towers have opened including the 49-storey CIBC Square and the 47-storey TD Terrace.

The new skyscrapers have increased the amount of office space in the core by 7.8 million square feet, or 9 per cent, according to Altus, a commercial real estate consulting firm. That occurred as demand dropped dramatically and tenants tried to get rid of their space on the sublet market.

Over the next two years, three more office towers will open in the financial district, including CIBC Square’s second 49-storey tower. The new additions will increase office space by another 2.5 million square feet, or 2.8 per cent, according to Altus.

As tenants move into their new offices at places like TD Terrace and CIBC Square, they are leaving their former landlords with space to fill.

For example, about 15,000 CIBC employees are expected to eventually move into CIBC Square, where the first tower opened in 2021 and has an availability rate of 0.9 per cent.

As the CIBC employees vacate their old spaces, that will leave holes in buildings such as Commerce Court, which has served as CIBC’s headquarters for five decades.

Prior to the start of the pandemic, when the downtown availability rate was 5.5 per cent, there was a raft of tech companies moving to the downtown core. So too were other established businesses, like Tim Hortons, which moved from the suburb of Oakville in 2019 to attract qualified employees. But today, there’s no longer a crush of companies competing for freshly vacated space.

In Scotia Plaza, one of its tenants was able to snag four of the highest floors of the building when Bank of Nova Scotia vacated the space.

Law firm Miller Thomson LLP will be moving to floors 63 through 66 from its current space four floors down and shrinking its office footprint.

The law firm negotiated its new 15-year lease during the pandemic when office space demand plunged. The firm’s managing partner, Kenneth Rosenstein, said it received favourable terms from its landlord KingSett Capital, including more branding within and outside the building.

This would not have been possible prepandemic. “We might have been able to get the space or comparable space. But I think it’s fair to say that it would have cost us more,” said Mr. Rosenstein. “Our timing worked out very well for us.”

The planned move to the top of Scotia Plaza has energized the culture and work environment at the firm, he said, adding he hopes it will lure more lawyers back to the office on a regular basis. “You really feel when you’re standing up there, that you are on top of the world, which is exactly the way we want our employees, our lawyers, our partners, and most importantly, our clients to feel,” he said.

According to CoStar, Scotia Plaza had an availability rate of 23.8 per cent in March.

KingSett’s chief asset management officer, William Logar did not comment on the rate, but said Scotia Plaza offers a strong combination of location and amenities in a building that is certified as zero carbon. He said his building completed 287,000 square feet of leasing last year. “Office deals are getting done,” he said in an e-mailed statement.

Every landlord has been showcasing its amenities. At TD Terrace, there will be an indoor garden at the top of the skyscraper; a games floor on the 37th with a big-screen TV and what the building calls its “retreat” on the 10th floor with yoga and spa elements.

At CIBC Square, the fourth-floor food court has a resident DJ every Wednesday and trivia on Mondays. It has an EV charging station, a bike room, showers, a gym and boasts lots of natural light.

“Following COVID, lots of employers are quite mindful as to how are we able to attract and have our employees come back to the office,” said Annie Houle, the head of Canada for Ivanhoé Cambridge, which developed and owns CIBC Square.

As building owners try to navigate this slump, understanding how the office sector got here is important to determining what comes next. The sharp rise in availability over the past four years reflects both a cyclical and structural slowdown.

On the first front, Canada’s economy has stagnated under the weight of high interest rates and weak investment by businesses. Last year real gross domestic product grew by just 1.1 per cent, the slowest pace outside of 2020 since 2016.

But the weakness in commercial real estate exposes demographic and technological forces that were already affecting demand for office space before the pandemic, as businesses sought to recruit younger employees by embracing tools that allowed more flexibility in how work got done.

To illustrate that, Mr. Gomez points to utilization rates, a measure of the amount of occupied space per office worker, which were already on the decline in both the U.S. and Canada as companies reassessed their needs.

“The pandemic has shone a light on how businesses use their office space,” he said. “They’ve realized they don’t need to take on more space and maybe they don’t need some of the existing space they already have.”

While vacancies have soared, so far Toronto’s downtown office market has avoided a reckoning in terms of building values. That’s because no one really knows what those towers are worth right now.

When a building gets sold, its sale price helps provide clarity about the valuation of other buildings around it. But deal volume fell sharply after 2021, leaving real estate investors in the dark.

However, in the U.S., deal activity has been picking up, in some cases resulting in shocking discounts. In April, an empty 16-storey tower in San Francisco, one of the hardest-hit commercial real estate markets in the U.S., fetched just US$6.5-million, a 90-per-cent drop from the US$62-million it sold for in 2016.

Aside from the sale of 121 King St. W. to Crestpoint early 2022, the only other major transaction in Toronto was the January, 2022, purchase of Royal Bank Plaza by a company controlled by Amancio Ortega, the Spanish billionaire owner of the Zara fashion retail chain, for $1.2-billion.

The site’s previous owners, the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board and Oxford Properties, a division of the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System, put the two towers that make up Royal Bank Plaza on the market the previous fall. OMERS had owned it since 1999; CPPIB since 2005.

One reason American cities are seeing more deals than Toronto comes down to the ownership structure of many of the city’s largest towers.

Institutional investors account for a much larger share of office ownership in Toronto compared with New York, for instance – 22 per cent versus just 4 per cent, according to CoStar. Meanwhile, companies that are primarily developers (and not just arms of institutional investors) own more than half of offices in New York City, compared with around one quarter in Toronto.

“We’re seeing the same underlying fundamental changes in office demand, utilization and availability in Toronto, but the U.S. has seen the market correct faster,” Mr. Gomez said. “On the face of it it looks like Toronto is immune, but the reality is it has to do with the capital structure of who owns the properties.”

Of the 47 buildings in the CoStar sample, 27 are fully or partly owned by five large investors. Here’s a look at how the ownership of parts of downtown Toronto breaks down.

Unlike developers and other owners that used debt to finance their office portfolios, and have come under intense pressure from rising interest rates that might force some to sell assets, large pension funds are better capitalized with more equity.

Some pension fund-backed owners argue their long-term investment horizon allows them to better weather storms like the one the commercial real estate market is facing now. It’s also true that office towers make up a relatively small portion of total assets for big pension funds, providing a buffer against a plunge in valuations.

“Vacancy has an impact on valuations, however vacancy has had a less significant impact on the valuation of CF’s portfolio, given the multiyear nature of our leases and the quality of our tenants,” said Mr. Iacono at Cadillac Fairview.

Where Toronto’s office sector is seeing sale offers pick up, and valuations drop, is among publicly traded real estate investment trusts that tend to own office buildings that are smaller or further afield.

Commercial REITs that own buildings in Toronto have seen their market valuations fall dramatically. Units of Dream Office REIT, which owns one of the buildings in the CoStar sample – State Street Financial Centre – among its 22 Toronto office buildings, have dropped 80 per cent since the start of the pandemic. Dream is reportedly exploring the sale of some of its Toronto buildings.

Meanwhile, Slate Office REIT units are down 88 per cent since their September 2019 peak, and the company is in the process of unloading parts of its portfolio to pay down debt.

“The market is speaking through the public market, but the argument for the private market is that the assets are of a different quality,” said Mr. Gomez.

That said, appraisers are still likely to seize on the trickle of smaller deals to help value the buildings in their portfolios.

“Even the owners who aren’t trading their buildings are going to have a sense of what those values are, and their stakeholders can then say whether they want to hold them for those kinds of returns or not,” Mr. Gomez said.

For the commercial real estate sector as a whole, the high interest rate environment has complicated the decision process for investors, said Ms. Houle at Ivanhoé Cambridge.

“If you have a term deposit at the bank paying you 5 per cent and you have an office that’s yielding you 5 per cent, where do you invest? The risk is not at all the same,” she said. “People have alternatives so it’s just taking a bit of time to rebalance the market dynamic.”

As grim as the picture looks for some corners of Canada’s largest commercial office market, Mr. Gomez remains optimistic about the future for Toronto’s downtown core. Location still matters, he argues.

“Downtown cores and the urban areas are vibrant and will continue to be that way as long as we have population growth,” he said. “But what people are doing downtown is different. It used to be live, work and play. Now it’s live and play. The work can be done elsewhere.”

The building models and maps in this article are based on tiles from the City of Toronto’s 3D Massing data set. Google Earth was used to verify the buildings’ locations visually based on their addresses, and we used the open source 3D software Blender to extract the 47 buildings we looked at and combine them with the data provided by CoStar.

Lead photo of Toronto’s skyline by Fred Lum; Editing by Joy Yokoyama; Visual development by Jeremy Agius.